Gold Award: Jin Young Choi

Yeom-La Daewang Crown-3, 2020, laser pointer, brooch, found object, LED, chain, resin, epoxy clay, wire,

silicone, 17″x20″x12.5″

Silver Award: Areum Yang

<Forest Series> 2020, acrylic, oil pastel, pencil on paper, 40x32in

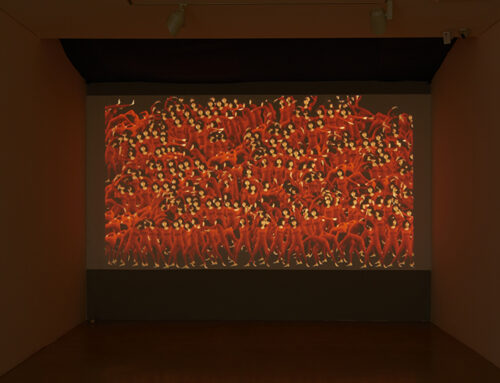

Bronze Award: Jiwon Rhie

Rice Set Theory_01, 2021, Plastic Rice, Participatory Installation, Dimensions Variable

Comments from the jurors

Leeza Meksin, Co-founder and Co-Director, Ortega Y Gasset Projects | Assistant Professor, Department of Art, Cornell University

Jin-Young Choi‘s sculptures reflect an integration of traditional Korean motifs with contemporary technology, as well as a merging of prehistoric animal imagery with post-human sensibilities. The works encompass statuary, wearable art such as helmets and jewelry, and kinetic sculpture with lights, hand-held devices and projections. Shamanic animal masks alluding to cave paintings and rituals are combined with plugged-in pods a-la Cronenberg’s 1999 film eXistenZ. The Sci-fi qualities fuse in surprising ways with the decorative embellishments creating a fresh forecast for future modalities. The sheer variety of materials employed by Choi is in itself a testament to resourceful ingenuity, suggesting survivalist strategies and a foreboding of what the future holds.

Areum Yang‘s expressive paintings exhibit both an economy of means and a cohesion of vision. These large scale works employ areas of loosely applied paint balanced with calligraphic use of dry brush, while portraying figures caught up in contortionist or fleeing postures. Painting Number 3 shows an exciting exploration into alternative planes within the picture plane – suggesting screens and virtual reality as universal themes now inextricably linked to the human condition. In the background of a starkly monochromatic painting Number 6 Yang presents a diagrammatic structure that skillfully and effortlessly alludes to a high rise building, suggesting that our love of the grid, and perhaps our obsession with order has gotten us into a prison-like cell.

Jiwon Rhie‘s architectural interventions speak to notions of belonging and assimilating to new environments. IKEA furniture items are made at once useless and poetic by being miter-fitted to staircases, banisters, door frames and closets, anthropomorphized like a vine covering a brick building. Disposable furniture brings to mind student life as well as the immigrant struggle to survive in a new possibly hostile environment. It also alludes to the makeshift nature of the symbiosis between human-made and natural elements, materials and structures. Rhie’s _Instant Forest_ works repurpose shipping materials and use images of custom forms slapped on packages sent from Korea by her mother. Collectively the work explores the nuanced ways in which our identities shift and meld into new forms through proximity to institutions and navigation of national and cultural norms.

Hallie Ringle, Hugh Kaul Curator of Contemporary Art at the Birmingham Museum of Art

Areum Yang Using a combination of pencil, pastel, and oils, Areum Yang’s paintings memorialize her everyday experiences. Yang renders her figures in a loose, gestural style that at times allows her figures to emerge from the canvas with perfect clarity and in others dissolve into amorphous masses. Yang is completely unburdened by the figurative/abstract binary, choosing instead to meld both styles of painting, allowing her to explore the emotional experiences of her subjects.

Jin Young Choi’s sculptures come from an imagined apocalyptic future, where past knowledge is preserved and communicated through his shamanistic sculptural forms. Combining simplistic electronics with highly complicated technology and found objects, Choi’s composite forms reference religion, perception, and the passage of time. Called “Digital Shaman” Choi envisions each of these sculptures as protective forms, meant to be used to symbolize a new, hybrid culture.

Jiwon Rhie’s practice combines disparate materials as means representing the complex negotiations of her experience immigrating to New York from Korea. In one work, Rice Set Theory, Rhie literally alters the landscape of the gallery by pouring plastic rice into thin lines that form borders, referencing systems of classification that contain significant areas of overlap. Rhie then asks the audience to walk around the installation, disrupting her highly-ordered system and betraying its borders as ultimately superficial. Other works, like Hi, Nice to Meet You combine functional, mass-produced future, and interior spaces, rendering both useless. Like Rice Set Theory, Hi, Nice to Meet You changes the gallery as much as it’s governed by it. By combining its form with the gallery, it both refuses any suggestion of functionality and forms new ways of existing in these spaces.

Marshall Price, Ph.d Senior Curator of Contemporary Art at Duke University

Jin-Young Choi creates technology-inspired sculptures that appear to have simultaneously been excavated from a past civilization and sent to us from a dark, dystopian future. Many of the artist’s works appear as devotional or ecclesiastical objects from a techno-centric temple in which digital connectivity and surveillance are customary, even obligatory. They are shamanistic in nature and function as a talisman for a post-natural, or perhaps even post-human, world, in which the lines between humanity and the digital realm are blurred. In doing so, these sculptures ominously question the relationship between culture and technology and raise larger questions about our anthropocentric world. Choi’s inventive combination of digital technology with intrinsically analogue materials results in mesmerizing, if cautionary, objects.

Areum Yang makes medium- and large-scale paintings and drawings that elicit a certain universal empathy. While they are figurative in nature and rooted in the human experience and condition, these works do not necessarily illustrate identifiable moments in time or specific events, but instead present the dynamics of emotions, sentiments, and other ephemeral states of being. Yang deftly uses the formal qualities of the material to create her dream-like sequences and, as a result, makes delightfully ambiguous scenes populated by familiar yet vague shapes and characters. These scenes, some of which appear as fantastical landscapes, others as quiet solitary interior scenes, allow for an expansive range of subjective interpretations and are not limited to any one specific reading.

Jiwon Rhie uses furniture, domestic spaces, and non-art objects such as rice and customs forms to explore issues of transculturalism and identity. In some works, the artist uses generic modern furniture placed in unexpected areas of a house. The modified furniture blends seamlessly with walls, bannisters, and other architectural spaces. In doing so, Rhie’s work creates a cognitive dissonance in the viewer that forces us to question our understanding of spatial relationships. On a deeper lever, however, this work may be understood as a metaphor for the difficulties and dynamics of navigating transcultural relationships. Other series, such as Instant Forest, is a very personal essay on the artist’s Korean immigrant experience. Garments and domestic objects (bedding, for example) are constructed from customs forms and visually articulated in a poignant and relatable way.